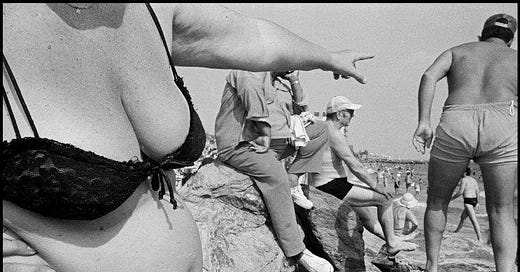

Waifish anemics with thin, unpolished nail beds love to photograph those freeform, sculptural women on the beach in Italy. You know, the ones that always grace vacation carousels, artfully zoomed in—all red and oiled and weathered and smoking—flesh bulging over and under black triangles with faces masked behind giant sunglasses. “How freeing—to age and sag and spread with such wild abandon!” The waifish anemics with thin, unpolished nail beds pen their captions (in so many words). “Now, these are real women.”

“Real” is a broad spectrum that means many things that people either cannot or will not say aloud. Sometimes, “real” is a euphemism for “without alteration.” Other times, it means “in defiance of societal beauty standards.” These are good things when properly owned and self-professed.

My agent forwards casting calls for “real women,” and sometimes I book the jobs too. Sometimes, I get to be the raw, unedited image that receives clapping emojis and accolades on the brand’s social media page. “It’s so nice to see real women for a change. Brava!” Of course, these are not the comments of waifish anemics with thin, unpolished nail beds—I’m not red and oiled and bulging enough (yet) to be artwork for them. I’m just imperfect—a cautionary tale of what could happen if the inner commands of self-motivation and control were to abandon their posts, like the Roman guards at Jesus’ tomb. These are the comments of women who are real in their own respect and hope that if enough of the world becomes real, then something will be solved and settled (I am one of these women).

Of course, there are always negative comments, too. “This is your answer to our rallying cry for depictions of real women? What—because of her twisted teeth and broad upper arms and furrows? This is not a real woman!” This is sometimes said by women who are neither red nor oiled but bulging perhaps (in reality or within their own perception) and lacking the desire to be this without apology on a beach in Italy (a valid concern, as the risk of becoming artistic fodder for some waifish anemic with thin, unpolished nail beds is ever-present). Sometimes, conversely, it is said by women who are untethered to physical bodies altogether—just hands typing away all day long in protest of everyone and everything and somehow nothing at all. I sometimes debate whether people can see the flaws that haunt me with my eyes closed, but these experiences will always set the record straight.

In the name of decency, it’s polite to sift through the insult and retrieve the hidden compliment. What they’re really saying is: “While you may be sufficiently flawed elsewhere, you are not flawed enough for this!”

I will tell you what I think most often when I gaze at these raw, unedited images of myself: I don’t want to be radical—I want to be the enviable, unrealistic standard—digitally liquified and smoothed and tightened for the sake of fantasy and profit. No one tells you to straighten your spine or lift your chin when the creative eye behind the image is trained on composition and intrigue over beauty—when the goal is to present something brave and unrefined. I cry out from these images—“Help! I’m a slave to the almighty dollar—I’m pimping my twisted teeth and broad upper arms and furrows to pay the rent! Somebody airbrush me!”

No one asks you if you want to be radical when you simply exist with twisted teeth and broad upper arms and furrows. No one asks if you want to be artwork when you’re red and oiled and weathered and smoking. But women in this life must always face the consequences of their actions and do so with grace and say, “Thank you very much! I was wondering what the whole world was thinking about me!”

Bruce Gilden - Coney Island, Woman on beach pointing at a man near her (1982)