PROCESS

I don’t read, and I’m told this makes me an asshole. Not always, not even often, but one man said it, and that was enough for me to brand it onto my backside.

“How do you expect anyone to read your writing if you don’t read theirs?” The man asked when I told him.

It wasn’t an inquisitive tone—he wanted me dead. We had been forced together at a party, having both been identified as “writers” by a well-meaning mutual. We should have been locked in separate rooms first and brought out to meet one another slowly over many days, like the introductory process used to acquaint an old cat with a new kitten. He hated my scent from the very start.

“Well, I—I don’t expect anyone to read my writing…” I stumbled and tripped. “But I also don’t believe art should be quid pro quo.”

“Why don’t you read?”

This time, it was an interrogation, like he didn’t entirely believe me or thought it was a gimmick. I was just another pick-me girl, aching to be unique for her contented illiteracy.

“I can’t read—other people’s styles infect me, and then I don’t know who I am. It’s not worth the time it takes for me to reconfigure myself and remember. I can’t help it—I’m a thief. I read the Beatniks in high school and thought I was a heroin addict on a big bus to nowhere for two whole years, and I wrote about America and the weariness of the road.”

This was the truth, and he understood it then.

“Well, maybe don’t read my novel.”

“I won’t. I promise.”

He didn’t precisely call me an asshole, but that was the word I heard telepathically when I looked into his eyes. I told myself later that he wanted to sleep with me—that he couldn’t stand how cold and aloof I was, and it destroyed him in an instant. This helped.

Reading is fundamental—it makes you a better writer—no one disputes this, not even I. Or me. (You see the problem)

A friend gifted me a book: Bright Lights, Big City. She said I would like it, and I wanted to try. I read thirty-two pages and googled: What’s it called when a book’s protagonist is referred to with the pronoun ‘you’ instead of ‘I’?

This is apparently called second person singular—the entire book was written this way, which I know because I thumbed ahead. I had to stop then, or I would’ve become a club rat cokehead in New York City while just scraping by at my job as a journalist. I stopped reading after page thirty-two, but I lifted the form and wrote everything that way henceforth.

You.

You.

You.

You wrote a novel. It took a lot of time, growth, pain, and stretching. You hoped people would read your book even though you’re an asshole and haven’t read theirs. You also hoped they wouldn’t.

The writer’s block hit shortly after. You experienced the five stages of grief: Denial as you sat in front of the blank page every day at 8 am, waiting. Anger with God for taking the one thing that gave you purpose. Bargaining—again with God—who may have stopped listening after the way you spoke to him in anger. Depression—warm and soft, welcoming you back like you never left. Then, finally, acceptance. When you resolved that maybe you were never a writer to begin with, and even if you were, you never would be again.

Another close friend prescribed that you read Miranda July. A total stranger echoed this, and you took it for a sign. This time, you got wise—you bought the audiobook on your boyfriend’s Audible account.

“As long as you’re using it, I’ll keep paying for it,” he said of the Audible account every month with the billing statement.

“I’m going to listen to The First Bad Man by Miranda July,” you told him triumphantly that month with the billing statement.

“Great. As long as you’re using it, I’ll keep paying for it.”

You carried on like this for whatever reason, even though a plan for usage had been concretely established. You took this to mean that he didn’t believe you and that he also thought you were an asshole.

You started it immediately and were surprised by the swiftness with which the story hooked into your mind. You found yourself circling the block with eggs, and meat, and cheese sitting beside you in a grocery bag just to get a little more. You muttered this surprise aloud to the eggs and meat and cheese, and they agreed that it was really something. But audiobooks are for the car, so you left it there when you turned off the ignition.

Soon, you found yourself itching to drive, desperate for a little more Miranda. You loved her voice—it sounded like your mother’s voice, but the way you heard it in the womb that one time. Muffled and deep, rumbling through flesh and muscle and amniotic fluid.

You tried to get your boyfriend to listen. He listened a little and said he liked it, but he wasn’t infected, so it didn’t stick. You were infected—you were sick as a dog.

The First Bad Man ended abruptly. It ended two blocks from home, which didn’t feel right. You were almost there—the last word could’ve settled gently in the dark quiet of your carport. Instead, it just slipped out the window. Gone, just like that.

You were feverish with infection. You read a page of your novel and couldn’t remember who wrote it. When you started to write again, you clipped your sentences.

Clip.

Clip.

Clip.

No more run-ons as stolen from Kerouac when you were sixteen. Miranda likes short. Short is good.

You decided the car was a good place to start, so you drove to the market and thought about writing. This started to work—soon, the moment the rubber hit the road and got rolling, so did you.

At a stoplight, you wrote:

Ideas build like a sneeze or climax. They feel urgent, pressing, and deeply necessary. If I don’t get it down, there’s a chance I’ll die. If I forget, my being will end, unraveling like an Achilles tendon with the quick blade of an ice skate.

The imagery was horrific—but you wanted to be open. You decided not to cull the weaker thoughts immediately, giving them a moment instead as you waited to see if they could stand and breathe on their own. You became desperate, holding onto the dregs—the burnt ends and entrails and gristle and such. You did it just in case it was your last meal. The last words you would ever write for all of eternity.

You’re all better now, but it’s not the same.

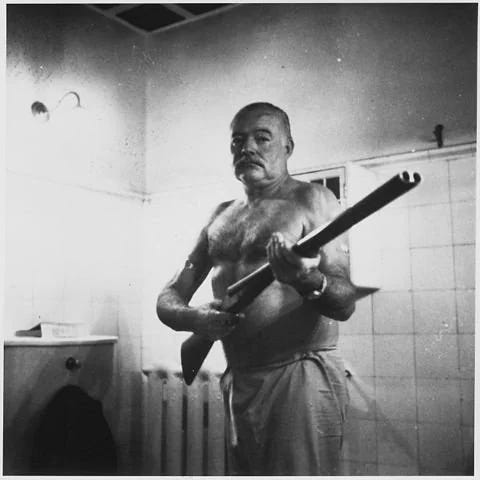

Ernest Hemingway with shotgun - (circa 1950)

<3